You have no items in your shopping cart. close

45 Schofield

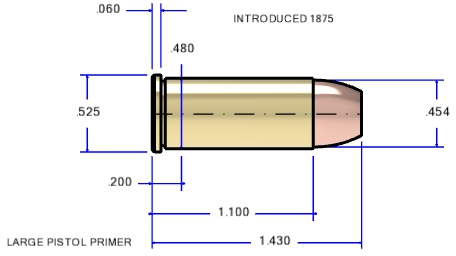

The .45 Schofield cartridge, also known as .45 Smith & Wesson, was introduced in 1875 for the Smith & Wesson Schofield revolver. It is a shorter version of the .45 Colt cartridge, designed to be compatible with the top-break action of the Schofield revolver.

The .45 Schofield was used primarily by the U.S. Army but was eventually overshadowed by the .45 Colt due to logistical reasons; while the Schofield could chamber the .45 Colt, it could not be done vice versa, leading to standardization on the longer .45 Colt.

The .45 Schofield cartridge features a rimmed case and typically fires a 230 to 250-grain bullet at approximately 730 to 800 feet per second. Its shorter length made it easier to extract from the revolvers, which was advantageous for cavalry troops.

Today, the .45 Schofield is considered obsolete, but reproduction ammunition is available for historical firearms enthusiasts and reenactors.

The .45 Schofield was used primarily by the U.S. Army but was eventually overshadowed by the .45 Colt due to logistical reasons; while the Schofield could chamber the .45 Colt, it could not be done vice versa, leading to standardization on the longer .45 Colt.

The .45 Schofield cartridge features a rimmed case and typically fires a 230 to 250-grain bullet at approximately 730 to 800 feet per second. Its shorter length made it easier to extract from the revolvers, which was advantageous for cavalry troops.

Today, the .45 Schofield is considered obsolete, but reproduction ammunition is available for historical firearms enthusiasts and reenactors.

question_answer Join Discussion (1 comment) add remove

Welcome to our cartridge knowledge base, featuring expert insights from M. L. (Mic) McPherson on a wide range of cartridges. Whether you're new or experienced, discover practical tips and share your field experiences to enrich our community. Please no disparaging remarks on other writers and no powder load data. Help shape a valuable resource for all enthusiasts. If you find anything factually incorrect, we want to hear about it! If you have any interesting comments or reloading tricks that you would like to share on this cartridge, share them here!

Please Log in to post a comment.- format_quoteformat_quote

| Die Sets |

|---|

| Lee Full-Length Sizing Die Set |

| 90323 (Carbide 3-Die set) |

| Lee Breech Lock Die Set |

| Lee Loader |

| Single Dies |

|---|

| Full-Length Sizing Die |

| Carbide Sizing Die |

| 90533 |

| Powder through Expanding Die |

| 91154 |

| Charging Die |

| Precision Bullet Seating Die |

| 92486 |

| Seating Die |

| 91194 92486 |

| Factory Crimp Die |

| Taper Crimp Die |

| Die Accessories |

|---|

| Micrometer Adjuster |

| 92150 |

| Guided Decapper |

| 91584 |

| Case Conditioning Tools |

|---|

| Case Length Gauge and Shell Holder |

| 90493 |

| Quick Trim Die |

| Presses |

|---|

| Reloader Press (50 RPH) |

| 90045 (Lee Reloader Press) |

| Hand Press (50 RPH) |

| Breech Lock Hand Presses |

| Challenger Press (50 RPH) |

| 90588 (Challenger III) 90050 (50th Anniversary Challenger Kit) 90030 (Challenger Kit) |

| Classic Cast Press (50 RPH) |

| 90998 (CLASSIC CAST PRESS) |

| Value Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| 90932 (4-hole Turret Press with Auto Index) |

| Classic Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| 90304 (Classic Turret Press Kit) 90064 (Classic Turret Press) |

| Ultimate Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| 91910 (5 Station Ultimate Turret Press) 92097 (6 Station Ultimate Turret Press) |

| Pro 1000 Press (500+ RPH) |

| PRO 1000 |

| Pro 4000 Press (500+ RPH) |

| 90900 (Pro 4000 Press Only) |

| Six Pack Pro Press (500+ RPH) |

| 91823 (Six Pack Pro Reloading Press) |

| Shell Plates and Holders |

|---|

| Priming Tool Shell Holder |

| 90272 (#14) |

| Universal Press Shell Holder |

| 90001 (R14) |

| X-Press Shell Holder (APP) |

| 91547 (#14) |

| Pro 1000 Shell Plate |

| 90065 (Pro 1000 Shell Plate #14L) |

| Auto Breech | Pro 4000 Shell Plate |

| 90802 (Pro 4000 Shell Plate 14) |

| Six Pack Pro Shell Plate |

| 91848 (14L) |

| Inline Bullet Feed |

|---|

| Inline Bullet Feed Die |

| 91997 (45CAL) |

| Inline Bullet Feed Kit |

| 92009 (45 CAL) |

| Inline Bullet Feed Magazine |

| 92016 (Large Inline Bullet Magazine) |

| Bullet Casting |

|---|

| Classic Bullet Sizing Kit |

| Breech Lock Bullet Sizer and Punch |

| Bullet Molds |