You have no items in your shopping cart. close

30-40 KRAG (30 U.S.)

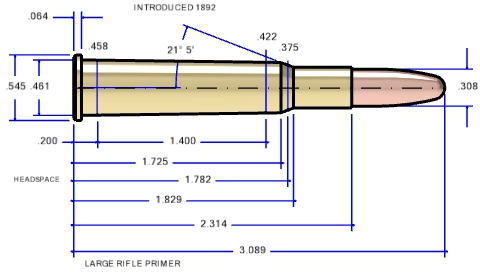

The .30-40 Krag, also known as the .30 U.S. or .30 Army, is a rifle cartridge that was introduced by the U.S. Army in 1892. It was the first smokeless powder round to be adopted by the U.S. military. The cartridge features a rimmed design and was originally designed for use in the Krag–Jørgensen bolt-action rifle, which was the standard service rifle for the U.S. Army until it was replaced by the Springfield M1903 in the early 20th century.

The .30-40 Krag typically uses a .30 caliber (7.62 mm) bullet that weighs around 220 grains, although other bullet weights have been used. The muzzle velocity is approximately 2,000-2,200 feet per second, depending on the specific load.

Use cases include military applications during its service period, as well as hunting medium to large game. The .30-40 Krag is noted for its relatively mild recoil and good accuracy. While no longer standard military issue, it remains popular among collectors and vintage firearm enthusiasts. It is also used by some hunters who prefer its historical significance and adequate performance for game such as deer and elk.

The .30-40 Krag typically uses a .30 caliber (7.62 mm) bullet that weighs around 220 grains, although other bullet weights have been used. The muzzle velocity is approximately 2,000-2,200 feet per second, depending on the specific load.

Use cases include military applications during its service period, as well as hunting medium to large game. The .30-40 Krag is noted for its relatively mild recoil and good accuracy. While no longer standard military issue, it remains popular among collectors and vintage firearm enthusiasts. It is also used by some hunters who prefer its historical significance and adequate performance for game such as deer and elk.

question_answer Join Discussion (1 comment) add remove

Welcome to our cartridge knowledge base, featuring expert insights from M. L. (Mic) McPherson on a wide range of cartridges. Whether you're new or experienced, discover practical tips and share your field experiences to enrich our community. Please no disparaging remarks on other writers and no powder load data. Help shape a valuable resource for all enthusiasts. If you find anything factually incorrect, we want to hear about it! If you have any interesting comments or reloading tricks that you would like to share on this cartridge, share them here!

Please Log in to post a comment.- format_quoteformat_quote

| Die Sets |

|---|

| Lee Full-Length Sizing Die Set |

| 92398 |

| Lee Micrometer Neck Sizing Die Set |

| Lee Breech Lock Die Set |

| Lee Ultimate 4-Die Set |

| Lee Loader |

| Single Dies |

|---|

| Full-Length Sizing Die |

| 91073 Ez X Expander: SE2169 |

| Sizing Die |

| Neck Sizing Die |

| Charging Die |

| 90194 (Long Charging Adapter) |

| Precision Bullet Seating Die |

| 92275 |

| Factory Crimp Die |

| 90843 (Collet Style) |

| Die Accessories |

|---|

| Micrometer Adjuster |

| 92215 |

| Guided Decapper |

| 91580 |

| Case Conditioning Tools |

|---|

| Case Length Gauge and Shell Holder |

| 90137 |

| Quick Trim Die |

| 91354 |

| Presses |

|---|

| Reloader Press (50 RPH) |

| 90045 (Lee Reloader Press) |

| Hand Press (50 RPH) |

| Breech Lock Hand Presses |

| Challenger Press (50 RPH) |

| 90588 (Challenger III) 90050 (50th Anniversary Challenger Kit) 90030 (Challenger Kit) |

| Classic Cast Press (50 RPH) |

| 90998 (CLASSIC CAST PRESS) |

| Value Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| Classic Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| 90304 (Classic Turret Press Kit) 90064 (Classic Turret Press) |

| Ultimate Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| Pro 1000 Press (500+ RPH) |

| Pro 4000 Press (500+ RPH) |

| Six Pack Pro Press (500+ RPH) |

| Shell Plates and Holders |

|---|

| Priming Tool Shell Holder |

| 90205 (#5) |

| Universal Press Shell Holder |

| 90522 (R5) |

| X-Press Shell Holder (APP) |

| 91538 (#5) |

| Pro 1000 Shell Plate |

| Auto Breech | Pro 4000 Shell Plate |

| Six Pack Pro Shell Plate |

| Inline Bullet Feed |

|---|

| Inline Bullet Feed Die |

| 91999 (30CAL) |

| Inline Bullet Feed Kit |

| 92011 (30CAL) |

| Inline Bullet Feed Magazine |

| 92015 (Medium Inline Bullet Magazine) |

| Bullet Casting |

|---|

| Classic Bullet Sizing Kit |

| 90038 |

| Breech Lock Bullet Sizer and Punch |

| 91512 |

| Bullet Molds |

| 90362 (C309-113-F Double Cavity Mold) 90364 (C309-120-R Double Cavity Mold) 90366 (C309-150-F Double Cavity Mold) 90367 (C309-160-R Double Cavity Mold) 90368 (C309-170 F Double Cavity Mold) 90369 (C309-180-R Double Cavity Mold) 90370 (C309-200-R Double Cavity Mold) |