You have no items in your shopping cart. close

17 Remington

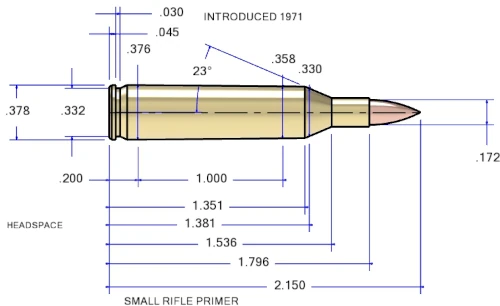

The .17 Remington is a small-caliber, high-velocity, centerfire rifle cartridge introduced by Remington Arms Company in 1971. It is based on the .223 Remington case, necked down to .172 inches (4.37 mm) to accommodate a .17 caliber bullet.

The cartridge is known for its extremely high velocity, often exceeding 4,000 feet per second (1,220 meters per second), and its flat trajectory. The .17 Remington is primarily used for varmint hunting and small game hunting. Its high velocity and small bullet diameter contribute to explosive impact on small targets, resulting in minimal pelt damage, which is particularly favored by fur hunters.

The .17 Remington's performance makes it suitable for shooting small targets at long distances, but its lighter bullets are more susceptible to wind drift compared to larger caliber bullets. Additionally, the barrel may require more frequent cleaning due to the high velocities, which can lead to fouling.

The cartridge is known for its extremely high velocity, often exceeding 4,000 feet per second (1,220 meters per second), and its flat trajectory. The .17 Remington is primarily used for varmint hunting and small game hunting. Its high velocity and small bullet diameter contribute to explosive impact on small targets, resulting in minimal pelt damage, which is particularly favored by fur hunters.

The .17 Remington's performance makes it suitable for shooting small targets at long distances, but its lighter bullets are more susceptible to wind drift compared to larger caliber bullets. Additionally, the barrel may require more frequent cleaning due to the high velocities, which can lead to fouling.

question_answer Join Discussion (1 comment) add remove

Welcome to our cartridge knowledge base, featuring expert insights from M. L. (Mic) McPherson on a wide range of cartridges. Whether you're new or experienced, discover practical tips and share your field experiences to enrich our community. Please no disparaging remarks on other writers and no powder load data. Help shape a valuable resource for all enthusiasts. If you find anything factually incorrect, we want to hear about it! If you have any interesting comments or reloading tricks that you would like to share on this cartridge, share them here!

Please Log in to post a comment.- format_quoteformat_quote

| Die Sets |

|---|

| Lee Full-Length Sizing Die Set |

| 90770 (2-Die set) |

| Lee Micrometer Neck Sizing Die Set |

| Lee Breech Lock Die Set |

| Lee Ultimate 4-Die Set |

| Lee Loader |

| Single Dies |

|---|

| Full-Length Sizing Die |

| 91028 Ez X Expander: SE1378 |

| Sizing Die |

| Neck Sizing Die |

| 91000 Decap Mandrel: NS2909 |

| Charging Die |

| Factory Crimp Die |

| 91571 (Collet Style) |

| Die Accessories |

|---|

| Micrometer Adjuster |

| 92215 |

| Guided Decapper |

| 91574 |

| Case Conditioning Tools |

|---|

| Case Length Gauge and Shell Holder |

| Quick Trim Die |

| 90435 |

| Presses |

|---|

| Reloader Press (50 RPH) |

| 90045 (Lee Reloader Press) |

| Hand Press (50 RPH) |

| Breech Lock Hand Presses |

| Challenger Press (50 RPH) |

| 90588 (Challenger III) 90050 (50th Anniversary Challenger Kit) 90030 (Challenger Kit) |

| Classic Cast Press (50 RPH) |

| 90998 (CLASSIC CAST PRESS) |

| Value Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| 90932 (4-hole Turret Press with Auto Index) |

| Classic Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| 90304 (Classic Turret Press Kit) 90064 (Classic Turret Press) |

| Ultimate Turret Press (250 RPH) |

| 91910 (5 Station Ultimate Turret Press) 92097 (6 Station Ultimate Turret Press) |

| Pro 1000 Press (500+ RPH) |

| PRO 1000 |

| Pro 4000 Press (500+ RPH) |

| 90900 (Pro 4000 Press Only) |

| Six Pack Pro Press (500+ RPH) |

| 91823 (Six Pack Pro Reloading Press) |

| Shell Plates and Holders |

|---|

| Priming Tool Shell Holder |

| 90204 (#4) |

| Universal Press Shell Holder |

| 90521 (R4) |

| X-Press Shell Holder (APP) |

| 91537 (#4) |

| Pro 1000 Shell Plate |

| 90653 (Pro 1000 Shell Plate #4S) |

| Auto Breech | Pro 4000 Shell Plate |

| 90630 (Pro 4000 Shell Plate 4) |

| Six Pack Pro Shell Plate |

| 91838 (4S) |

| Inline Bullet Feed |

|---|

| Inline Bullet Feed Die |

| Inline Bullet Feed Kit |

| Inline Bullet Feed Magazine |

| Bullet Casting |

|---|

| Classic Bullet Sizing Kit |

| Breech Lock Bullet Sizer and Punch |

| Bullet Molds |